Podcast: Play in new window | Download | Embed

A brief overview and spotlight on the real Blues musician who’s name adorns an upcoming film on Netflix that features Academy Award winner Viola Davis and the last filmed performance of Chadwick Boseman. #marainey #blues #bluesmusic

More than 75 percent of all correspondence to me is concerning an artist or recorded audio that someone has heard about in visual media. This week, Netflix will debut a filmed version of August Wilson’s 1982 Pulitzer Prize winning play Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom.

Yes, I get that people could easily just look these things up on the internet. Nonetheless, it brings me nothing but pride that someone thought I might have some kind of answer for them, especially considering the format I use to present audio to the programs fans, which joins together an overview instead of just individual clips that one has to wade through.

To the best of anyone’s research, all of which owes a great deal to Sandra R. Leib’s highly detailed work in the book Mother of the Blues: A Study of Ma Rainey (1983, University of Massachusetts Press. ISBN 0-87023-334-3), Rainey was possibly only the second Black woman ever recorded. She cut 94 songs, many of them in the Blues genre, but others that also would be considered Pop or novelty records, all of which were popular during the Jazz age of the 1920’s. She also wrote a great deal of her own lyrics, and is considered one of the first true “Blues” artists. According to legend, it was also Rainey that coined the term “Blues” to describe her music.

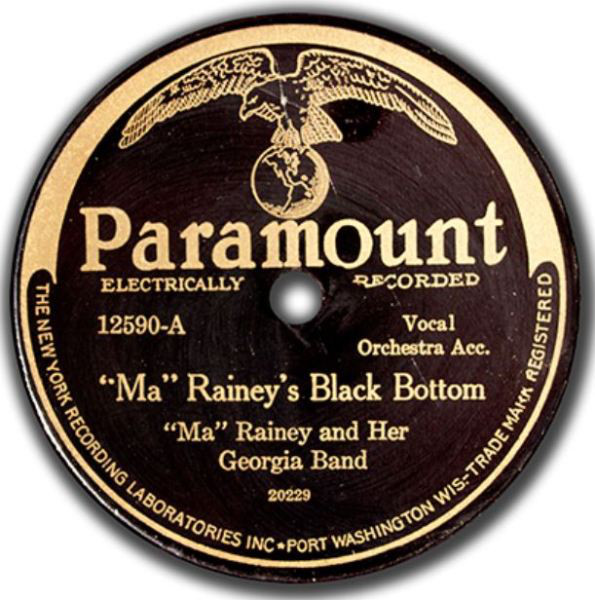

She recorded for the Paramount label, based out of Wisconsin. She was at least 36 years of age, which is almost unheard of for a new artist then or now. Paramount would record some of the most influential and early Blues music in history, which also included Blind Lemon Jefferson, Louis Armstrong and Thomas Dorsey, the latter one of the most prolific writers and performers of secular music and religious songs in history. (Their entire catalogue has been re-issued in two massive volumes several years ago by Third Man Records, owned by Jack White.)

Born Gertrude Pridgett in 1886 in either Alabama or Georgia (census records and personal accounts are conflicting), she was married in 1904 to Will “Pa” Rainey. She toured the chitlin’ circuit (a series of black-owned venues in the South and the East Coast) relentlessly, first in minstrel shows (a type of vaudeville-like entertainment that depicted Black people in usually degrading and racist settings, often in song, dance and comedy skits) for years, honing her craft. In 1923, she recorded her first sides for Paramount in Chicago, which also happens to be the setting of the play and film.

After the success of Mamie Smith on Okeh Records out of New York City in 1920, music labels, still a fairly new business enterprise, were keen to record Black musicians, which were popular among the white record buying public. Her first recordings weren’t originally led by men, but by Lovie Austin, a Black female bandleader out of Chicago and considered one of the finest players of Blues piano of the era.

Rainey would become a popular recording and touring figure; however, her legacy has been overshadowed by Bessie Smith, who outsold her in the 1920’s. (Rainey’s honorary title was “Mother of the Blues; Smith’s was “Empress of the Blues”.)

Smith would continue to record and lay claim to also being the best-selling Blues artist of the 1930’s as well. Rainey, on the other hand, left the recording business altogether when her contract with Paramount wasn’t renewed. She went back home to Georgia, where she ran no less than three different clubs, often playing in them or on tours until 1935, when she decided to retire from live performing.

By the end of the decade, with the stock market crash and the beginning of the Great Depression, the entire recording industry was almost completely wiped out. The Jazz Age had died, and it would take several years for the economy to start to recover, leaving many musicians, especially Black ones, without a means to survive as entertainers, as labels focused on newer forms of music and trends to profit off of.

Rainey would die in 1939 from a heart attack, and depending on which source biographical material was cited, was either 53 or 57. In addition to Leib’s work on her, Angela Davis also penned the title Blues Legacies and Black Feminism: Gertrude Ma Rainey, Bessie Smith, and Billie Holiday (1999, Vintage. pp. 40, 238. ISBN 978-0679771265), with both books detailing that in addition to Rainey being one of the first Black women and Blues musicians ever recorded, she was possibly one of the first bisexual persons ever recorded.

Several of Rainey’s songs contained references to lesbian encounters, such as “Prove It On Me Blues”, a radical concept for any recording of the era, illustrating there was more to Rainey than just being a song and dance footnote in music history, but a pioneer in every sense of the word.

First Part

- Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom, 1927, 78 RPM 10″ single, matrix #20229

- Chain Gang Blues, 1925, 78 RPM 10″ single, matrix #2372

- Misery Blues, 1927, 78 RPM 10″ single, matrix #4707

- Black Eye Blues 1928, 78 RPM 10″ single, matrix #20898

- Countin’ The Blues, 1924, 78 RPM 10″ single, matrix #1927

- Daddy Goodbye Blues, 1928, 78 RPM 10″ single, matrix #20878

- Weepin’ Woman Blues, 1926, 78 RPM 10″ single, matrix #407

Finale

- Prove it On Me Blues, 1928, 78 RPM 10″ single, matrix #20665

Love to you all.

Ben “Daddy Ben Bear” Brown Jr.

Host, Show Producer, Webmaster, Audio Engineer, Researcher, Video Promo Producer and Writer

“Copyright Disclaimer Under Section 107 of the Copyright Act 1976, allowance is made for ‘fair use’ for purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching, scholarship, and research. Fair use is a use permitted by copyright statute that might otherwise be infringing. Non-profit, educational or personal use tips the balance in favor of fair use.”