Podcast: Play in new window | Download | Embed

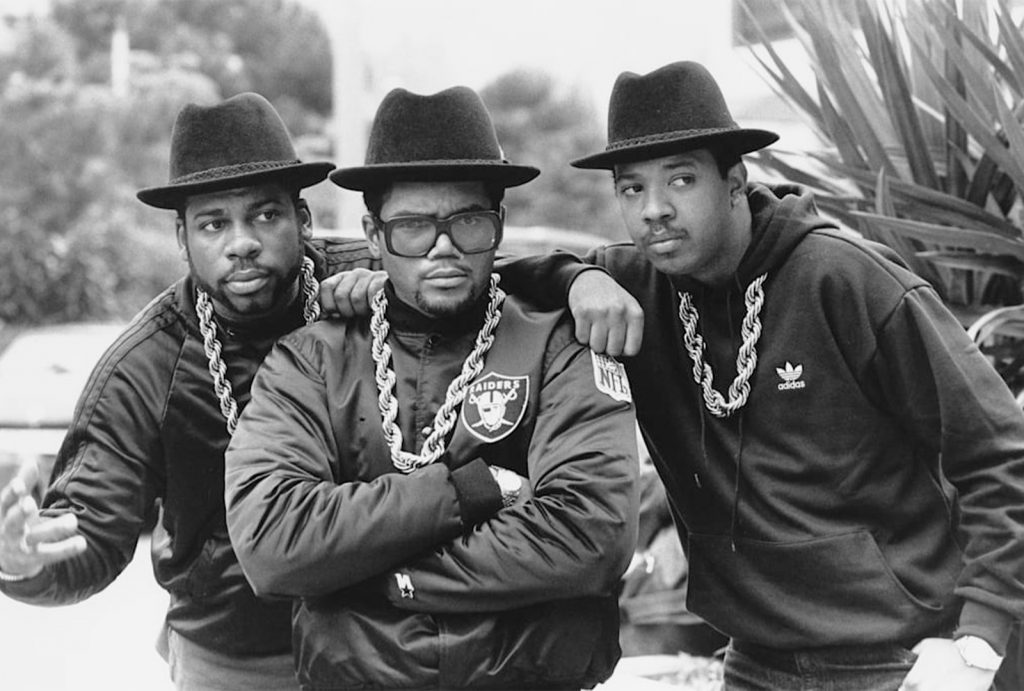

Three years after the initial wave of Hip-Hop singles released on vinyl made a sudden impact, the genre went into completely different directions at a rapid pace, much of this stirred on by advancements in technology and a refocus on lyrical themes. #oldschool #blackmusic #hiphop #electronic #bboys #bgirls

WARNING: There are no ballads in this program. Repeat, no ballads.

Well, that didn’t take long. Based upon the incredible positive feedback from last week’s Early Hip-Hop 79-81 program, presenting part two in the series this week, featuring tracks from 1982 and 1983.

The nascent Hip-Hop genre, which was only three years into official, vinyl releases, went though a massive transformation by 1982. There were still the party songs and the boasting raps, but technology was changing this scene at a pace never before seen in music history. Additionally, some of the lyrics started to reflect the struggles of daily Black life in America not seen in almost a decade after the end of the era of the message song, and some dealt with themes that were literally out of this world, which were partially a reflection of the technology. The latter would encompass themes that would later be called Afrofuturism.

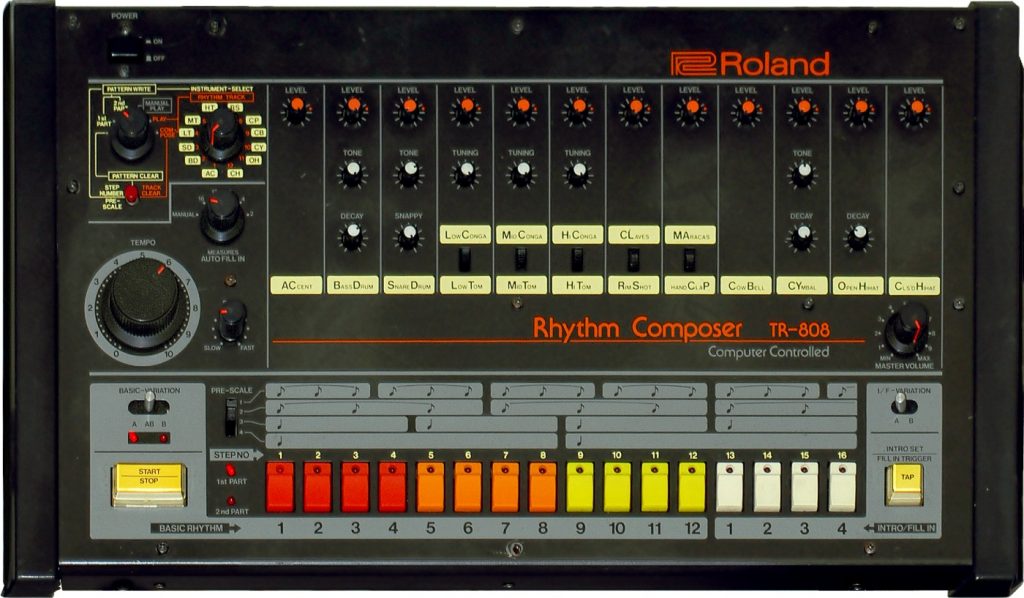

The advancements were keeping pace with the rest of society: digital technology was here and infiltrating every single part of our lives in the early 1980’s. Digital recording techniques were becoming more commonplace, with affordable polyphonic keyboards and drum machines (made by companies such as Yamaha, Roland and Korg) and small, portable studio equipment (with Tascam being a favorite) meant anyone with a little money and in a small amount of space could release industry standard recordings.

Along with these advancements were the still-expensive but becoming-more-affordable digital samplers, such as the Fairlight, which would alter Hip-Hop forever, as digital sampling is still the primary use today for this task. This also meant that Hip-Hop immediately started to leave behind its Disco and early-70’s Funk roots for a type of music soon to be known as Electro, which also started to alter the sound of Black R&B and overall dance music as well. Interestingly, later 1970’s Funk groups, such as Parliament/Funkadelic, were becoming a major source of inspiration.

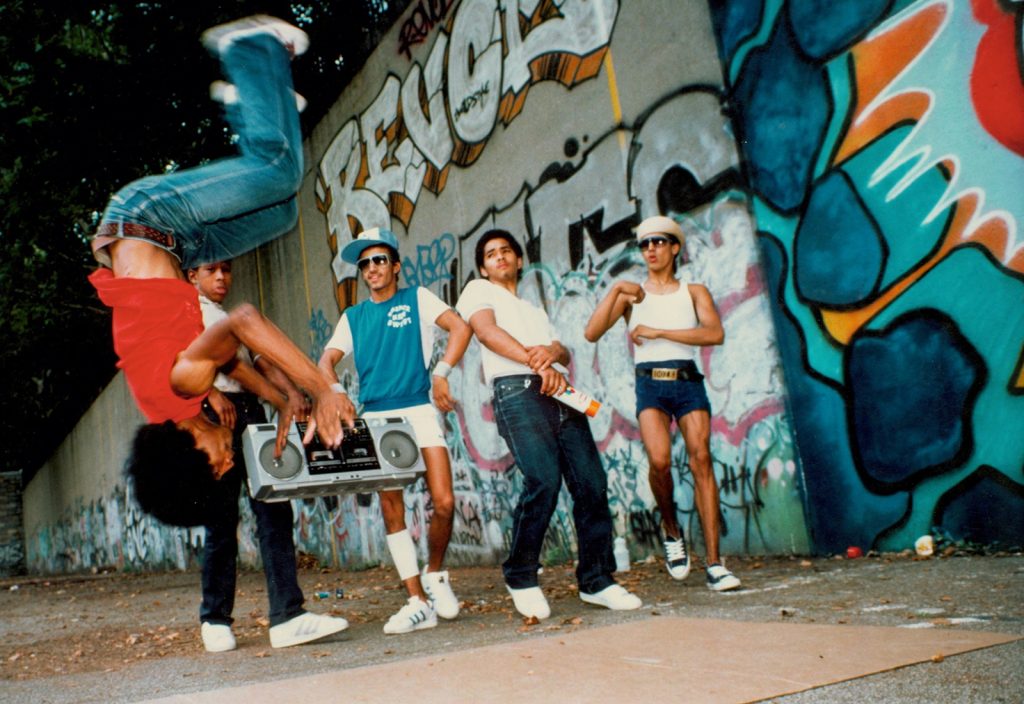

This was able to give rise to a Hip-Hop phenomenon that wasn’t about Rappers, songwriters, musicians or DJ’s, but that of the Breakers, known by the mainstream as Breakdancers with its purveyors known in the scene as B-Boys and B-Girls. These were, along with Graffiti/Aerosol artists, the most visually important statement of the early Hip-Hop scene.

Breaking was a type of highly original, syncopated post-modern dance derived from Black culture (opposed to a white Classical origin, such as ballet) that at times used acrobatics akin to gymnastics. It could be performed solo, in tandem with a partner or in groups. Its first real introduction to mainstream media occurred in 1982 with the film Wild Style, directed by avant-garde artist Charlie Ahearn, a man who helped bring what was then called “street culture” to the attention of the highbrow New York City art scene.

Again, with technology being a major force in the rise and popularity of the Breakers, large portable stereos known as boomboxes became the norm, often replete with at least one cassette deck and a built-in equalizer. These dancers now were no longer tethered to the street parties of yore, but could, with enough D-size batteries, take their performance art anywhere they wished.

Hip-Hop culture responded in kind, with all sorts of new styles of tracks, many of them incredibly beat heavy and filled with long instrumental passages, and these became the de facto choice for Breakers. An interesting development of this was that the music started to get faster from some recording acts, and slower from others, with an often increasing use of spare soundscapes to emphasize the new tech signaling an almost clean break from the lush strings and horn charts of Disco that once was its heartbeat.

An interesting byproduct was the use of distorted vocals, which previously had to use vari-speed tape players and voice boxes (the latter extensively used by Peter Frampton on his mega-selling Frampton Comes Alive album in 1976), but could now be altered digitally with the touch of a button.

In addition to these developments, Hip-Hop was starting to be taken seriously by influential mainstream critics, and the once neighborhood block-party feel-good music of New York City was creeping into other genres, including Electronic Dance, Jazz Fusion, Soul and Pop music, which also meant that white people were becoming fascinated with this new future in music, and were already in groups with Black members or releasing singles in their own.

I am told by those far better in the know, knowledge and understanding and respect for Hip Hop and its roots are vital. This is the second part in a series of shows presented intermittently that focus on some fan favorites and key tracks in Hip-Hop’s first decade.

First Part

- Rockit (album version), 1983, Herbie Hancock, Future Shock

- The Message, 1982, Grandmaster Flash and The Furious 5, 12″ single A-side

- Clear, 1983, Cybotron, 12″ single A-side

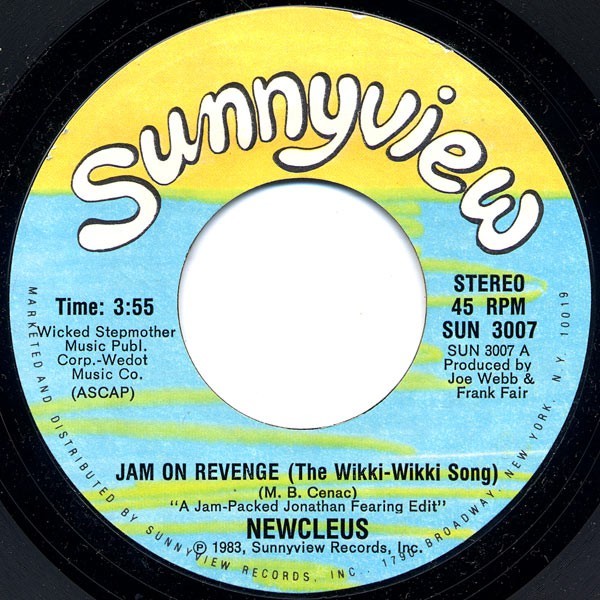

- Jam On Revenge, 1983, Newcleus, 12″ single A-side

Second Part

- It’s Like That (7″ version), 1983, Run-DMC, 7″ single A-side

- Al Naafiysh (The Soul), 1983, Hashim, 12″ single A-side

- Smurf Trek, 1982, Chapter III, 12″ single A-side

Finale

- Planet Rock, 1982, Afrika Bambaataa & The Soul Sonic Force, 12″ single A-side

Love to you all.

Ben “Daddy Ben Bear” Brown Jr.

Host, Show Producer, Webmaster, Audio Engineer, Researcher, Videographer and Writer

Instagram: brownjr.ben

Twitter: @BenBrownJunior

LinkedIn: benbrownjunior

Design Site: aospdx.com

“Copyright Disclaimer Under Section 107 of the Copyright Act 1976, allowance is made for ‘fair use’ for purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching, scholarship, and research. Fair use is a use permitted by copyright statute that might otherwise be infringing. Non-profit, educational or personal use tips the balance in favor of fair use.”