Podcast: Play in new window | Download | Embed

The last decade has primarily seen Hip-Hop artists focus on singles in place of albums, much like in its early history, but Kendrick Lamar has carved out his place as the rare current artist who maintains a foot in both worlds.

NOTE: this program may contain language and subject matter some find objectionable.

Recently, on the Showtime talk show program Desus and Mero, guest Chris Rock had not heard of YouTube’s biggest star of 2020, YoungBoy Never Broke Again, because he is interested in “album artists”. I was shocked to learn that Rock was actually 3 years older than your host at age 55, but I was not surprised at his comment. The album-as-artistic-statement is a relic of a bygone era that currently has very little love in the business it seems. Digital singles, which are now at their shortest length in a decade on the Billboard charts, have overtaken the marketplace.

What really shocked me about Rock’s interview is that another person around my age is still interested in exciting and different new music.

Yes, artists are still releasing albums, and Hip-Hop artists have been releasing mixtapes for years. However, today, the physical album/cassette/CD in sheer terms of sales has been primarily the sole realm of Rock artists, a genre which has taken a back seat in the new millennium. Rock artists, particularly veterans, can still move physical product, and lucratively. But in terms of overall impact, due in no small part to streaming, they are a fraction of the overall market.

“Who’s the new album artists, you know what I mean?”, Rock said. “The ups, the downs, the weird single that you know—the weird album track that you know was never gonna be a single, but you love it.” And then Rock went on to say that his favorite new artists currently making albums like this are J. Cole and Kendrick Lamar.

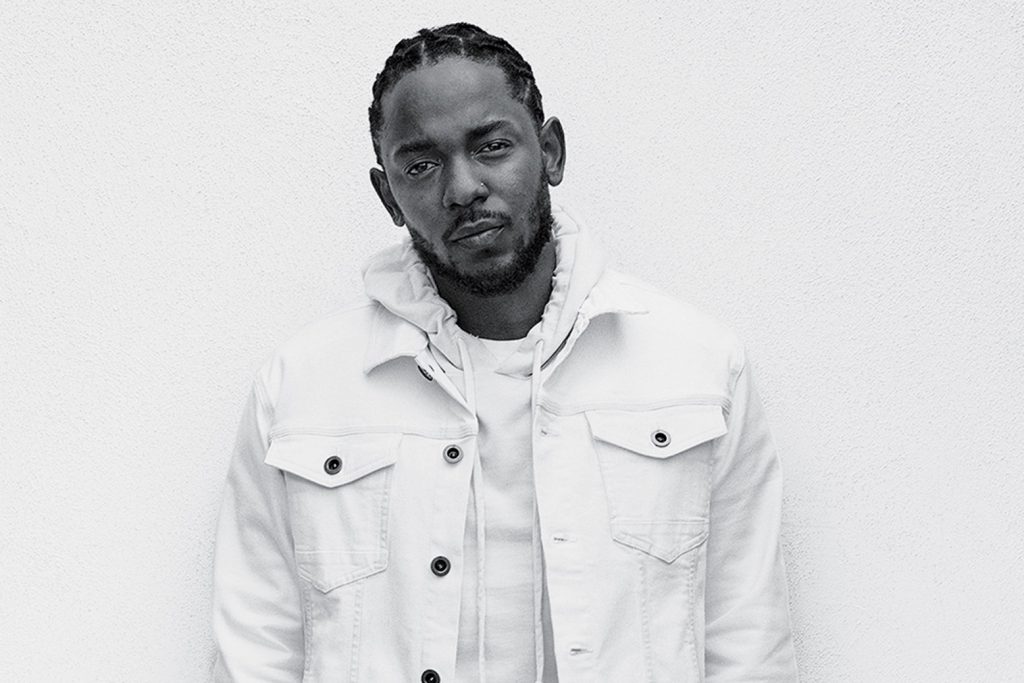

Kendrick Lamar Duckworth is from the Los Angeles city of Compton, the son of Chicago transplants. His initial bio is rather uninteresting: he grew up poor, not involved in gangs or drugs, loved cartoons and sports, was a shy child and a straight-A student. However, his life was changed by witnessing the filming of the video “California Love” by Tupac Shakur featuring Dr. Dre in 1995. In the words of female astronaut Sally Ride, “You can’t be what you can’t see.”

He did, however, get into trouble with his friends from the neighborhood as a teen, and several times were on the wrong end of a firearm from the police, experiences he channeled into his early songs. Lamar has called the L.A.P.D. “the biggest gang in California.”

“I don’t do black music, I don’t do white music. I do everyday life music.”

– Kendrick Lamar

Starting off as an indie artist with the moniker K-Dot, he worked his craft tirelessly and ended up signing to a local independent label in nearby Carson, Top Dawg Entertainment. And, much like a classic rock artist paying their dues, worked on releases and opened on tours for more established artists. His first releases under his own name would not come until about ten years ago.

With his second full-length album, Good Kid, M.A.A.D. City, along with major label distribution, Lamar saw his career take off almost exponentially. Lyrically, his work also became more personal, detailing his experiences just attempting to survive in the U.S. as a Black person. Sonically, his work has also stretched out immensely, incorporating Soul music, Free Jazz and Spoken Word. Several of his songs are sometimes two, three or even four times the length of today’s current charting singles.

Accolades have come from all sectors, including a Pulitzer Prize (the first non-classical or non-jazz artist to do so), with sales to match. With his subsequent releases, which include the soundtrack to the biggest film of 2018, Black Panther, Lamar has also become a symbol of the socially conscious rapper, something considered a throwback to the late-1980’s, much like Rock artists of the late-1960’s are viewed.

Though he hasn’t released any new music under his name in over a year, and only contributed a verse to a new Busta Rhymes album track last month, his songs have been a part of the cultural moment in 2020, especially “Again”, which has been a rallying cry for many in the Black Lives Matter movement. Old folks, this is your chance to hear and possibly understand just a small part of what Chris Rock is talking about.

First Part

- Alright, 2015, To Pimp a Butterfly

- Untitled 07/Levitate, 2016, Untitled/Unmastered

- Bitch, Don’t Kill My Vibe (Remix), 2012, Good Kid, M.A.A.D City (expanded version) (featuring Jay Z.)

- Rolling Stone, 2011, Setbacks by ScHoolboy Q. (Black Hippy: ScHoolboy Q, Ab-Soul, Jay Rock and Kendrick Lamar)

- Genocide, 2015, Compton by Dr. Dre (featuring Kendrick Lamar, Marsha Ambrosius and Candice Pillay)

- Humble, 2017, DAMN

Second Part

- All The Stars, 2018, Black Panther soundtrack (Kendrick Lamar featuring SZA)

- HiiiPower, 2011, Section 80

- Look Over Your Shoulder, 2020, ELE2: The Wrath of God (Busta Rhymes featuring Kendrick Lamar)

- Vanity Slaves, 2009, The Kendrick Lamar EP

Finale

- Mortal Man, 2015, To Pimp a Butterfly

Love to you all.

Ben “Daddy Ben Bear” Brown Jr.

Host, Show Producer, Webmaster, Audio Engineer, Researcher, Video Promo Producer and Writer

“Copyright Disclaimer Under Section 107 of the Copyright Act 1976, allowance is made for ‘fair use’ for purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching, scholarship, and research. Fair use is a use permitted by copyright statute that might otherwise be infringing. Non-profit, educational or personal use tips the balance in favor of fair use.”